How can one learn to play with finesse and with a real understanding of the score? Avoid repeated note-playing, aim yo be “vocal” and introduce the odd emoji.

Many piano students fall into the trap of spending hour a day practicing technical exercises and studies without simultaneously developing their ear, and their understanding of how to the music they strive to master is constructed. To be a good pianist we first need to be a good musician. One of the 20th century’s great teachers of musicians, Nadia Boulanger, used a variety of teaching methods including traditional harmony and counterpoint, score reading at the piano, analysis, and sigh-reading (using solfeggi) to instil discipline and craft into those who were accepted into her studio. In this article, I will look at some of the main skills all musicians need to grow and develop.

Singing

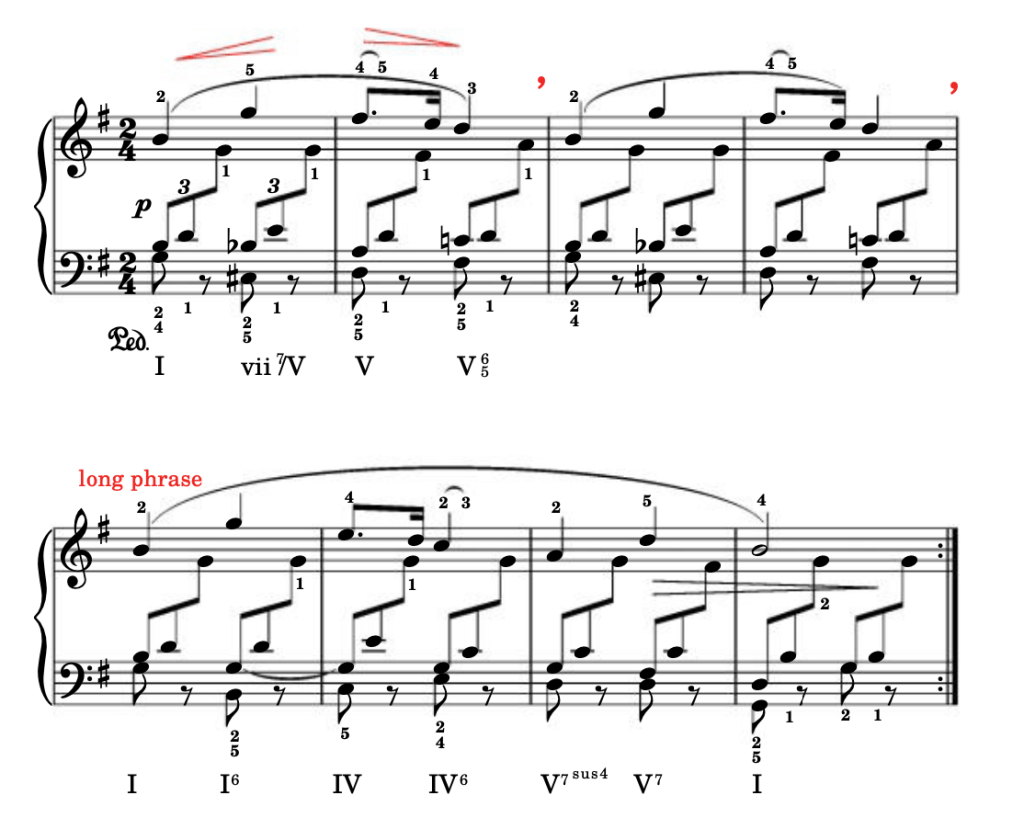

Ongoing ear training is a required component of a formal musical education, starting with singing. Singing should be a part of piano lessons from the beginning stages to the advanced level; if we can not sing a line, it means we haven’t really heard it – and therefore we can’t really play it. Where are the high and low points of a particular phrase? Where does the line want to breathe? Without such awareness we might be able to push down the right keys at the right times, but we won’t be expressing much. The extra ingredient of that elusive cantabile tone so coveted by pianists is intonation, the ability to move from one note to the next not only in tune, but also applying subtleties of colouring and timing that replicate the human voice. For a singer or a violinist, a wide interval usually takes a small fraction of time; the pianist needs to create that illusion at the piano. When you learn a new piece, first sing the main melodic lines. Concentrate on what you hear inside, imagine the melody as exactly as possible before trying to sing it. Repeat the process a few times away from the piano to help develop your inner hearing. After you have imagined the melodic line, replicate it on the keyboard – and only then add the other ingredients (accompaniment, balance, tone, etc.). In this example from Schumann’s ‘Of Foreign Lands and People’ (from Kinderszenen), feel the intonation in the rising minor 6th from the B to the G. Your singing voice, which never lies, will almost certainly want to make a small diminuendo to the end of the second bar, after which you will need to breathe. You are unlikely to sing bars 3 and 4 (an exact replica of bars 1 and 2) in the same way – perhaps you’ll do it softer, or with greater intensity. The next phrase is four bars in length, requiring one breath.

I have included a harmonic analysis in case this is meaningful to you. You could equally label the chords by their letter names (G major, diminished 7th on C#, D major, etc.), or just be aware of the expressive effects of some salient features, such as the diminished 7th chord in bars 1 and 3, and the suspension in the middle voice in bar 7. A little bit of analysis goes a long way in deepening the learning process, involving more parts of the brain than are required simply to move the fingers in response to what the eye sees on the page. Here are a few aspects you might notice:

- We are in the key of G major

• The phrase structure is 2+2+4

• The second phrase is an exact replica of the first

• Each phrase begins on the melody note, B (the mediant)

• The three-part texture features a top melody supported by a light bass line on the main beats, with a broken chordal middle part divided between the hands

After playing the melodic line by itself, shaping it as expressively as possible, add the bass line and the pedal. Next, play the triplet accompaniment alone with no pedal, listening for evenness between the hands. Thereafter, play the bass line together with the accompaniment, with the pedal. If you are up for a challenge, try omitting the melody line and singing it instead, while playing the two accompanimental parts. When you are ready to put the piece together, you will need to listen critically to the sounds you are creating, especially the balance between foreground and background.

Maintaining a steady pulse

The ability to establish and maintain a steady pulse is essential for all music making. Some pianists complain about a weak sense of rhythm, and resort to the metronome to help fix this. A metronome pumps out the beat, but rhythm is something much more alive, more flexible, more physical. If you struggle to keep a steady pulse, a certain amount of metronome practice can be useful (provided you are actually playing 100 per cent together with it), but counting out aloud while playing is, in my opinion, a much more useful exercise. When we count as we play not only can we allow the music to breathe naturally, we can also include the sort of ebb and flow that we describe as rubato, but which inhabits all music to some extent. No performance of any piece should be robotically metronomic, and an over-reliance on metronome practice kills the human qualities within the music.

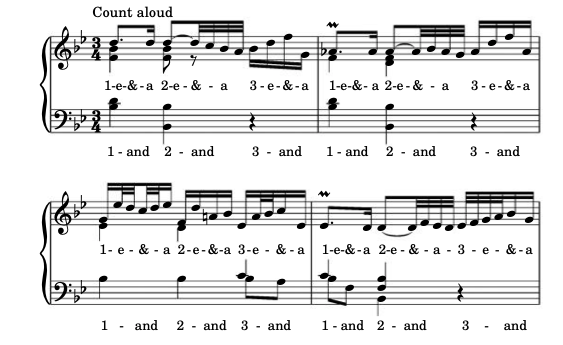

In the Sarabande from Bach’s B flat Partita, I have subdivided the main crotchet beats in half and in quarter. Can you vocalise the counting as you play? You might want to start

with a skeleton version – the main events but without the embellishments, gradually adding more detail until you have the complete picture.

For those who need a more structured approach to rhythm work, I can highly recommend Dalcroze Eurhythmics classes, as well as Robert Starer’s book, Rhythmic Training, and Paul Hindemith’s (more advanced) Elementary Training for Musicians.

In his monumental book, The Art of Piano Playing, Heinrich Neuhaus devotes the first chapter to ‘the artistic image of a musical composition’. Music making is not about merely playing the notes accurately and correctly, that’s just a starting point. Our aim as we practise should be to discover and communicate the musical message as we feel it. It can be helpful to put into words what a particular passage expresses, for example: con amore, some descriptive adjectives, or even an emoji. When we work with groups of pianists, I have often asked the class to close their eyes and imagine a movie screen in front of them. As I play, I invite them to see whatever it is they see on this screen. Afterwards, as we go round the room, it is uncanny how similar the stories are. If the player is intent on telling a story or painting a picture in sound then the listener will pick up something tangible from the performance. It might not be exactly what the player has in their imagination, but it will have sparked the listener’s imagination. I did this recently with Satie’s Gymnopédie No 3; the words that came back to me included ‘sad’, ‘lonely’, ‘crying’, etc., showing me that I had succeeded not only in playing the notes but in communicating my take on Satie’s musical message.

My advice is not to think of the study of theory, ear training and reading at sight as separate activities that eat into your valuable practice time. If you can integrate these areas of musical literacy into your learning you will end up a far better musician, able to learn pieces more quickly and more thoroughly, with greater understanding. The good news is that musicianship classes are available at community colleges and evening classes here in the UK, and most major cities in the world ought to have similar resources. It is never too late to start!

For the Online Academy’s practical music theory course by Alejandro Jiménez, visit contact page.